How Emergency Services Respond to Major Incidents in the UK

When a major incident happens in the UK, emergency services activate structured response plans. This includes events such as a large fire, a serious transport accident, or a public safety threat. These plans are designed to protect lives and maintain order. These incidents can put sudden pressure on local resources. They require rapid deployment of police, fire crews, and ambulance teams. Hospitals and local authorities must work together. From the moment a 999 call is received, trained control room staff assess the situation. They dispatch the appropriate units to attend as quickly as possible.

Emergency response performance in the UK is measured against clear targets. For ambulance services, the national standard is to respond to the most life-threatening (Category 1) calls within an average of 7 minutes, and to reach 90 % of such calls within 15 minutes or less, though actual performance can vary by region.

The phones never stop. On average, UK police forces receive a 999 call every 3 seconds, and around 71 % of these are answered within the target of under 10 seconds. Fire and rescue services in England strive for rapid attendance. Recent data shows the average response time to primary fires at about 9 minutes and 13 seconds. This is the longest seen in several years. Dwellings are typically attended in around 8 minutes.

These figures highlight how complex and resource-intensive modern emergency response has become. Each incident triggers a multi-agency effort. This can include fires, collisions, and medical emergencies. Success depends on efficient logistics, clear communication, and rapid decision-making under pressure. While these services aim to meet their target times, actual on-scene arrival can be delayed. Factors such as traffic, weather conditions, and the incident’s scale can affect timely arrival.

Understanding these response metrics helps explain what happens behind the scenes when sirens sound and large-scale operations begin. It also underscores the critical importance of well-coordinated emergency systems in protecting public safety and saving lives, even as demand increases across the UK.

What Is Considered a Major Incident?

In the UK, a major incident is any event or situation with a serious impact on public safety. It also affects health or infrastructure. It requires a response that exceeds normal emergency service operations. These incidents either overwhelm local resources or demand significant coordination between multiple agencies.

Major incidents can occur suddenly. They can also develop over time. These incidents may affect a large number of people or critical services. Examples include:

• large-scale fires affecting residential or commercial buildings, such as the response to complex high-rise fires where multiple fire crews are needed

• serious transport accidents, including multi-vehicle motorway collisions or rail derailments requiring closure of major routes

• severe floods during winter storms that cause widespread road, rail, and property damage, as seen in recent UK winter weather events

• structural failures or dangerous building collapses that pose risks to public safety and require specialist rescue teams

• security alerts and suspected terrorist incidents where public spaces are evacuated and specialist units are deployed

• outbreaks of illness or contamination affecting public health and necessitating coordinated emergency action

An incident does not need to involve significant casualties to be classified as major. The key factor is the scale and complexity of the response required. It is more important than only the severity of individual injuries or damage.

When an incident is officially declared “major”, emergency services activate specially developed response plans. This allows senior commanders to request additional personnel, specialist equipment, and support from neighbouring regions or national agencies. Hospitals are alerted to prepare for incoming patients, and local authorities coordinate wider community support, transport management, and public communication.

Declaring a major incident also improves coordination and decision-making. All responding organisations operate under a shared framework. This allows them to prioritise life-saving action. They manage risks to the public and responders. They restore normal conditions as effectively and safely as possible.

The First Response

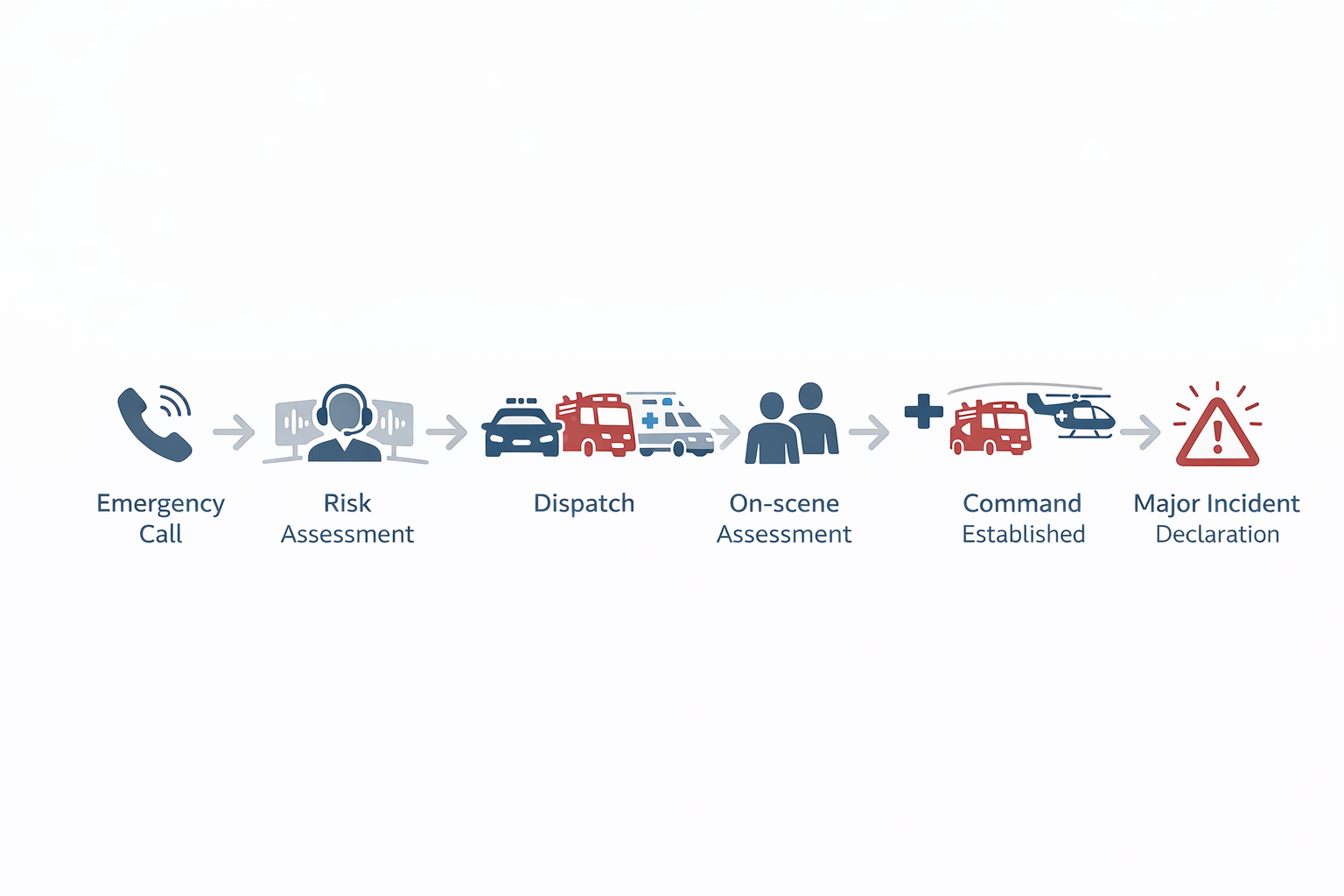

Regional control centres handle emergency calls in the UK. These centres are operated by police, fire and rescue services, and ambulance trusts. When a call suggests a serious or potentially life-threatening situation, call handlers follow strict assessment protocols. They gather key information, such as location, number of people involved, and immediate dangers. If a major risk is identified, emergency services respond rapidly. They coordinate by dispatching multiple services at the same time.

The first crews to arrive at the scene play a critical role. They carry out an initial assessment to understand the scale and severity of the incident and to identify any immediate threats. This early evaluation helps determine how the situation should be managed and whether additional support is required. Factors assessed at this stage typically include:

• the number and condition of injured or trapped people

• risks to the public, including nearby residents or passers-by

• fire, smoke, chemical, or structural hazards

• whether evacuation of buildings or surrounding areas is necessary

• traffic management and road closures to allow emergency access

Based on this assessment, commanders on the ground may request further resources. These can include additional fire engines, ambulances, or police units. They may also request specialist teams such as urban search and rescue, hazardous materials units, or air ambulance support.

If the incident is considered beyond normal operational capacity, senior officers present may make a formal declaration of a major incident. This declaration activates wider emergency plans and allows services to draw on regional or national support. Hospitals are alerted to prepare for casualties. Local authorities are informed. Command structures are expanded to manage the response more effectively.

This early phase of response is crucial. Rapid decision-making, clear communication, and accurate assessment help prevent further harm. They protect emergency workers. They also ensure that help reaches those most in need as quickly as possible.

Coordination Between Services

All UK emergency services operate under a shared framework known as Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Principles (JESIP). This system was introduced to improve cooperation between agencies during major incidents. It ensures that police, fire and rescue, and ambulance services collaborate efficiently. Local authorities and other responders also work together rather than in isolation.

JESIP is built around common principles, including shared communication, joint decision-making, and clear leadership at the scene. This approach reduces confusion, prevents duplication of effort, and allows resources to be used where they are most needed.

Command during a major incident is typically organised into three levels:

• Strategic – Senior leaders set overall objectives and long-term priorities, often operating from control centres away from the scene.

• Tactical – Managers coordinate resources and plan operations in the affected area, translating strategy into practical actions.

• Operational – Frontline responders carry out direct tasks on the ground. These tasks include rescue, medical treatment, and securing the area.

Each emergency service has defined responsibilities within this structure. Police focus on public safety, scene security, traffic management, and criminal investigation if required. Fire and rescue services deal with fires, hazardous materials, and rescuing people from collapsed or dangerous structures. Ambulance services provide emergency medical care, triage patients based on severity, and transport the injured to appropriate hospitals.

By working under a shared command framework, emergency services can respond more quickly. They can act even more effectively, even in complex or fast-moving situations. This coordinated approach is essential in large-scale emergencies. Clear leadership and cooperation can make a critical difference. They help in protecting lives and restoring safety.

Medical Response and Hospitals

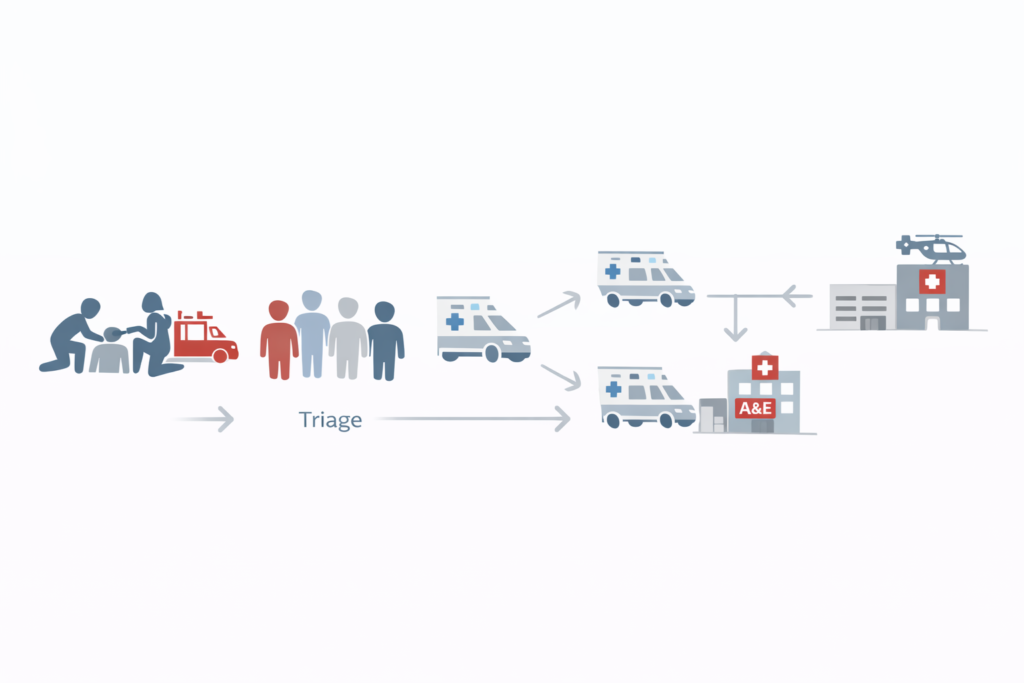

Ambulance services play a critical role in major incidents. They assess and prioritise patients based on the severity of their injuries. This process, known as triage, ensures that those with life-threatening conditions receive treatment first. Paramedics make rapid decisions at the scene. They determine who needs immediate care. They also decide who can safely wait, working under pressure to save lives.

In the UK, ambulance response times are closely monitored. The latest NHS England performance data sets a goal. This goal is to respond to the most life-threatening calls (Category 1) within an average time of 7 minutes. The aim is to reach 90% of these calls within 15 minutes. However, these targets are challenging to meet consistently due to demand and capacity pressures. For less urgent but still serious calls (Category 2), response times are often longer. These include cases such as suspected strokes or heart attacks. This reflects the operational strain on services.

When a major incident is declared, hospitals activate internal emergency plans designed to manage a sudden influx of patients. These plans allow hospitals to quickly expand capacity and prioritise emergency care. Actions may include:

• cancelling or postponing non-urgent appointments and procedures

• calling in additional doctors, nurses, and support staff

• opening extra emergency or assessment wards

• coordinating patient transfers with nearby hospitals to balance demand

Emergency departments work closely with ambulance services to ensure patients are taken to facilities best equipped to treat their injuries. To support this, the UK has a network of specialist Major Trauma Centres. There are 27 designated centres (as of 2024) across England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. These centres are equipped with the surgical teams and intensive care units required to manage severe trauma. This includes major head injuries, multiple fractures, and internal bleeding.

For example, during major incidents, patients with critical injuries may be directly routed to a nearby Major Trauma Centre. This approach is preferred rather than using a general A&E department. It shortens time-to-treatment and improves outcomes. These centres operate as part of regional trauma networks that coordinate between ambulance services and hospitals.

This coordinated medical response helps save lives during major incidents. By combining rapid triage, flexible hospital planning, and specialist treatment in trauma centres, the healthcare system is able to respond effectively even under sudden and intense pressure..

Public Communication

Clear and accurate communication is vital during major incidents. Keeping the public informed helps reduce confusion, prevent panic, and ensure that emergency services can operate safely and effectively. In the UK, authorities use multiple channels to share timely updates as situations develop.

Information is typically communicated through:

• national and local news outlets, which provide verified updates and official statements

• social media platforms used by police forces, fire services, ambulance trusts, and local councils

• official government and local authority websites

• emergency alert systems, including mobile phone alerts for serious or immediate threats

Messages are carefully coordinated to ensure consistency across agencies and to avoid the spread of misinformation. Updates may include details about road closures, transport disruption, evacuation zones, or changes to public services.

During major incidents, the public may be asked to avoid specific areas. They should follow safety advice. They may also need to remain indoors if there is a risk from smoke, hazardous materials, unstable structures, or debris. In some cases, residents may be instructed to evacuate or to keep doors and windows closed as a precaution.

Accurate information plays a key role in supporting emergency operations. When people follow official guidance, responders can reach affected areas more quickly. It reduces unnecessary pressure on emergency call centres. This helps protect both the public and emergency workers. Clear communication reassures communities that the situation is being managed. It ensures that reliable information will be shared as it becomes available.

Investigation and Recovery

Once the immediate danger has passed and the scene is made safe, the focus shifts. It moves from emergency response to investigation and recovery. Police and specialist safety agencies begin work to determine what happened. They investigate how the incident unfolded. They assess whether any laws, regulations, or safety standards were breached.

Depending on the nature of the incident, different UK investigation bodies may be involved. These can include the Health and Safety Executive. It investigates serious workplace accidents and industrial incidents. The National Fire Chiefs Council supports investigations into complex fires alongside local fire and rescue services.

Independent specialist bodies often examine transport-related incidents. These include the Rail Accident Investigation Branch for rail incidents. The Air Accidents Investigation Branch investigates aviation events. The Marine Accident Investigation Branch handles incidents at sea or in ports. These organisations focus on identifying causes and safety lessons rather than assigning blame.

Police forces continue parallel investigations where there is a possibility of criminal offences, working with prosecutors where necessary. Evidence such as witness statements, CCTV footage, vehicle data, and expert reports may be collected over weeks or months.

Alongside investigations, recovery efforts focus on supporting affected communities. Local councils and government agencies help coordinate practical and social support, including:

• arranging temporary or long-term housing for displaced residents

• repairing damaged roads, buildings, utilities, and public infrastructure

• supporting affected families through social services and community programmes

• restoring transport networks, schools, healthcare services, and local businesses

Once recovery is underway, long-term reviews are often carried out. These reviews assess how the incident was handled. They identify strengths and weaknesses in the response. Additionally, they recommend improvements to emergency planning, training, and coordination. Lessons learned are shared nationally to help reduce the risk of similar incidents in the future.

Training and Preparedness

UK emergency services regularly carry out large-scale training exercises to prepare for major incidents and disasters. These exercises are designed to test coordination between police, fire and rescue services, and ambulance teams. They also involve hospitals, local authorities, and other partners under realistic conditions.

One well-known example is Exercise Unified Response. It is a national multi-agency exercise coordinated across police, fire, and ambulance services. NHS services and local resilience forums are also involved. It focuses on testing joint decision-making and communication. It also evaluates command structures during large-scale emergencies, such as mass casualty incidents or infrastructure failures.

Fire and rescue services frequently conduct urban search and rescue (USAR) training exercises. These simulations involve collapsed buildings that occur after explosions, fires, or structural failures. These exercises test specialist rescue equipment, casualty extraction techniques, and coordination with ambulance and police services.

Flood response training is also common, particularly in areas prone to severe weather. Emergency services and local councils have carried out exercises. These exercises simulate widespread flooding. The simulations are similar to events seen during recent winter storms in England and Wales. These drills test evacuation planning, use of flood rescue teams, and support for displaced residents.

Transport-related scenarios are rehearsed through exercises involving rail operators, airports, and highways authorities. These exercises may simulate train derailments, tunnel incidents, or major motorway collisions. Emergency services practice managing casualties. They also secure scenes and work on restoring transport networks.

Hospitals and NHS trusts also engage in mass casualty and major incident exercises. These exercises test their ability to handle large numbers of patients at short notice. These drills may include activating emergency plans, expanding emergency department capacity, and coordinating with regional Major Trauma Centres.

Lessons learned from these exercises are reviewed and shared nationally. Findings are used to improve planning, update guidance, enhance communication systems, and refine equipment and training programmes. This continuous cycle of testing and improvement helps ensure that emergency services are better prepared for real incident.

Major incidents can happen without warning. The response’s effectiveness often depends on preparation done long before an emergency occurs. Regular training exercises help emergency services identify weaknesses, strengthen cooperation, and respond more confidently when real situations arise.

Although these exercises may take place quietly behind the scenes, they play a vital role in protecting the public. Understanding how emergency services train and prepare highlights the importance of investment in readiness. It also emphasizes teamwork and learning from past experiences to keep communities safer.