Gaza is emerging from the ruins of war. The road to reconstruction is already proving to be one of the most divisive challenges in the region’s modern history. It is also one of the most politically charged.

Bulldozers have begun clearing debris from the streets of Gaza City. Shattered concrete, twisted steel, and memories of once-bustling neighborhoods now define the landscape. In areas like Sheikh Radwan, entire blocks have been erased.

“This was my home,” says 63-year-old Abu Iyad Hamdouna, pointing to a heap of rubble. “At this rate, it could take 10 years to rebuild. I don’t think I’ll live to see it.”

Nearby, residents salvage what they can-bricks, furniture, anything usable-from the wreckage. “Removing the rubble take five years,” says Nihad al-Madhoun. He is a 43-year-old Gaza who has returned to his neighborhood for the first time since the fighting ended.

According to UN estimates, the destruction is almost unimaginable. Nearly 300,000 homes and apartments have been damaged or destroyed. The cost of reconstruction exceeds $70 billion. The Gaza Strip now holds an estimated 60 million tonnes of rubble, much of it contaminated with unexplored ordnance.

With so much devastation, the question of how Gaza should be rebuilt has sparked competing visions. People are debating who will oversee the rebuilding. These discussions stretch from Gaza City to Washington and beyond.

Homegrown vs. Foreign Visions

Gaza’s Hamas-appointed mayor, Yahya al-Sarraj, says the city has already begun the slow process of recovery. “People are reopening small shops and restaurants,” he says. “They deserve to live.”

Al-Sarraj supports a local initiative called the Phoenix Plan. It was developed by hundreds of Palestinian architects, engineers, and planners. The planning took over a year. The plan envisions rebuilding Gaza with modern infrastructure while preserving its social and cultural fabric.

“A foreign-imposed plan for reconstruction cannot exist,” says project contributor Yara Salem. She is a veteran development expert and former World Bank official. “We wanted to fill the vacuum with a Palestinian vision.”

Unlike proposals designed abroad, the Phoenix Plan was drafted by Gaza’s themselves, emphasizing local expertise and ownership. But its future is uncertain as international players-each with their own political agenda—compete for influence over Gaza’s post-war reconstruction.

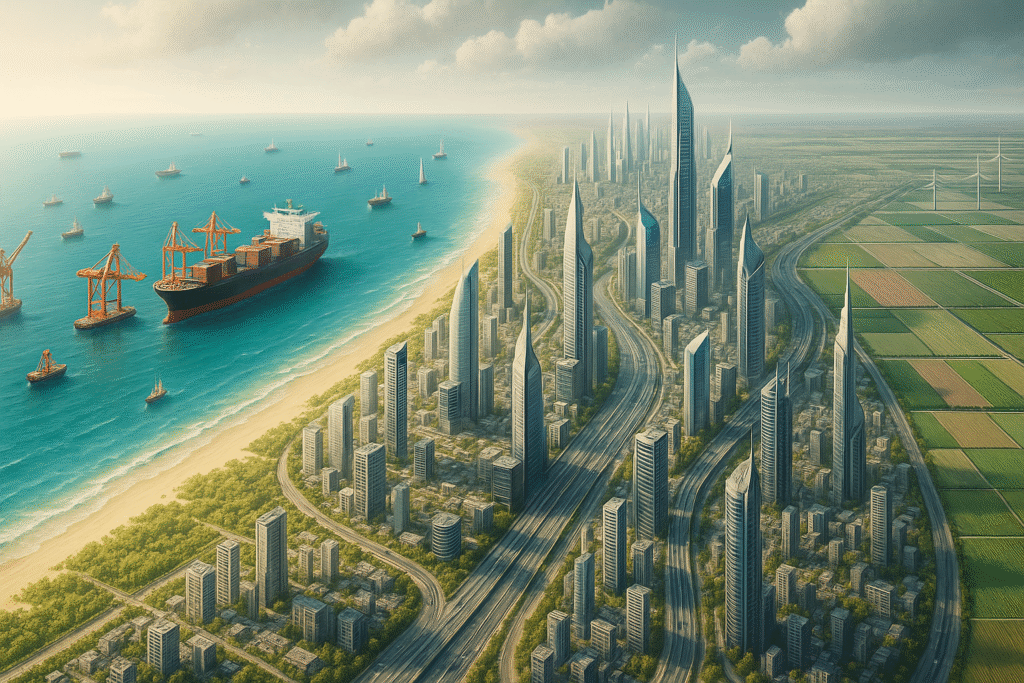

The “Gaza Riviera” and Foreign Ambitions

Former U.S. President Donald Trump has floated his own vision. He proposed a “Gaza Riviera,” a redevelopment project. This would turn the war-torn coastal strip into a luxury destination. He suggested the U.S. take a “long-term ownership position” in the territory. His son-in-law Jared Kushner described Gaza’s beachfront as “valuable real estate.” It one day thrive.

Trump’s team has linked this idea to his 20-point ceasefire proposal, which outlines a “Board of Peace” to oversee reconstruction. Reports have speculated that former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair is involved.

Another leaked plan, known as “Great”-short for Gaza Reconstitution, Economic Acceleration, and Transformation Trust—proposes a high-tech, AI-driven Gaza under U.S. trusteeship for a decade. American and Israeli consultants drafted it. It envisions “smart cities.” It even suggests “voluntary relocation” incentives for a quarter of Gaza’s population.

Critics have called these blueprints unrealistic and insensitive.

“These hallucinatory plans are risky. Raja Khalidi warns that Gaza could become an experiment in disaster capitalism. He is the head of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute. “Reconstruction must be led by Palestinians.”

Regional and Palestinian Proposals

The Arab League is led by Egypt. It has endorsed a five-year reconstruction initiative. This initiative emphasizes local participation and is similar in spirit to the Phoenix Plan. Meanwhile, the Palestinian Authority (PA) has unveiled its own blueprint. This plan seeks to reconnect Gaza with the West Bank. The aim is to create a future Palestinian state.

“Seventy percent of Gaza’s population are refugees,” says Estephan Salameh, the PA’s planning minister. “We must preserve Gaza’s soul and community identity.”

Salameh argues that any rebuilding effort should revive, not erase, the tight-knit neighborhoods that have defined Gaza for generations. “We want to rebuild Jabalia where it was,” he says, referencing one of Gaza’s largest refugee camps.

The Long Road Ahead

Experts warn that rebuilding Gaza will take decades, not years. “This is going to be an incremental process,” says Shelly Culbertson of the RAND Corporation. “Some areas will be rebuilt piece by piece, while others need to be razed and started from scratch.”

Beyond the logistics, political barriers remain enormous. Israel has said it will allow reconstruction only in areas it controls militarily. Donor nations like Saudi Arabia and the UAE are hesitant to invest. They need assurances that new infrastructure won’t be destroyed in future conflicts.

An Egyptian-hosted donor conference is expected, but no date has been set.

Meanwhile, for ordinary Gaza’s like Abu Iyad, daily survival overshadows the grand visions. “We just want water,” he says. “We’re building tents next to the homes we can no longer live in.

Leave a Reply